#Textiles of India

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Muslin, that diaphanous cotton of India, is steeped in a bleak history of colonialism, Imperialism, and human atrocity. That's a way to start a Monday, isn't it? But that's the thing about fashion history.

Looking at a gown like this, which dates from the late 1840s, it's easy to get lost in the beauty: the pattern, the layers, the absolute Romantic gorgeousness.

It is, undoubtedly, a work of art, making use of that thin, breathable fabric, with delicate ruching, a genius use of pattern, and a shape that's reminiscent of the 18th century.

The demand for muslin fabric was immense, bolstered by the impact of the British East India Company, beginning in the 18th century. The finest muslins were from the Dhaka region and 2000 thread count *made by hand*. Starting with Marie Antoinette and her famous chemise a la reine, the craze for muslin among the elites of Europe came at a devastating cost--eventually contributing to the loss of the art and the death of millions of people in the regions.

Because once Europeans figured out how to manufacture muslin on their own (as they did with silk, paisley, pashminas, etc) they stopped all trade with India.

And of course, the great irony is that Europeans didn't just take the art and design, but directly appropriated patterns, styles, and more. There's a reason "question beauty relentlessly" is the Thread Talk motto. Lots more info on the subject over at my blog.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

#threadtalk#historical costuming#silk dress#textiles#fashion history#costume#costume history#history of fashion#muslin#textiles of india

618 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weavers showcasing their intricately handwoven work, Kashmir, 1961 by Slim Aarons

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

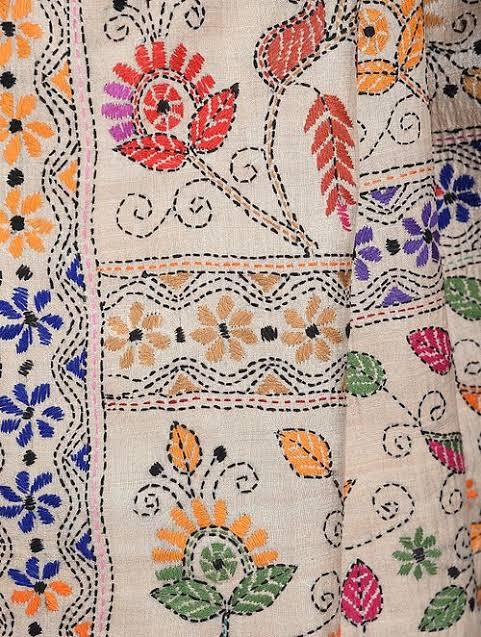

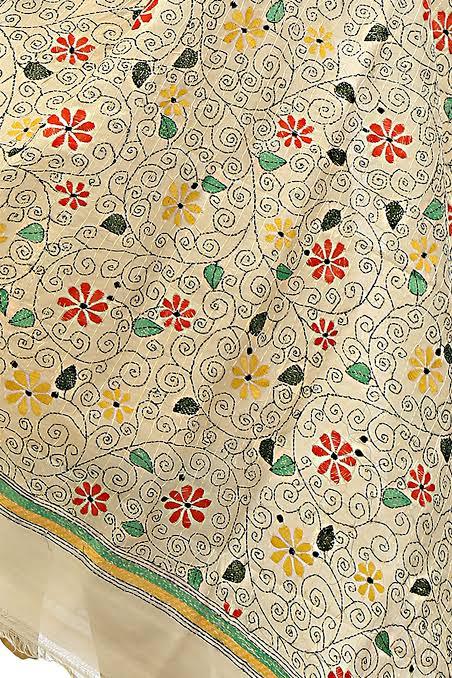

Kantha (Bengali: কাঁথা) is a form of embroidery originating in Bengal region, i.e. Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and parts of Assam. It has its roots in nakshi kantha, an ancient practice among bengali women of making quilts from old saris and rags by sewing them together. In modern usage, kantha generally refers to the specific type of stitch used. The kantha needlework is distinct and recognised for its delicacy. The stitching on the cloth gives it a slightly wrinkled, wavy effect. Today, kantha embroidery can be found on all types of garments as well as household items like pillowcases, bags and cushions.

While it is an increasingly diversifying art form, traditional kantha embroidery motifs are still sought after. Traditional kantha embroidery is two-dimensional and are usually of two distinct types: geometric forms with a central focal point, carried over from the nakshi kantha tradition and influenced by islamic art forms; and more fluid plant, floral, animal and rural motifs with stick-figure humans depicting folklores and rural life in Bengal.

1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 8 / 9 | textile series

#bangla tag#textiles#ots#kantha#nakshi kantha#bengal#bengali#bangladesh#india#embroidery#needlework#textile art#embroidery art#south asia#south asian

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dagger with Scabbard

Indian, Mughal 1605–27

The hilt of the dagger is constructed of heavy sections of gold over an iron core and its scabbard mounts are of solid gold. All the intricately engraved surfaces are set with gems and colored glass finely cut with floral forms. The designs closely parallel those in Mughal painting of the early seventeenth century, suggesting the dagger dates from the reign of Emperor Jahangir (1605–27), whose deep love of nature, especially flowers, is well documented in his memoirs, the "Tuzuk." The blade is forged of watered steel.

877 notes

·

View notes

Text

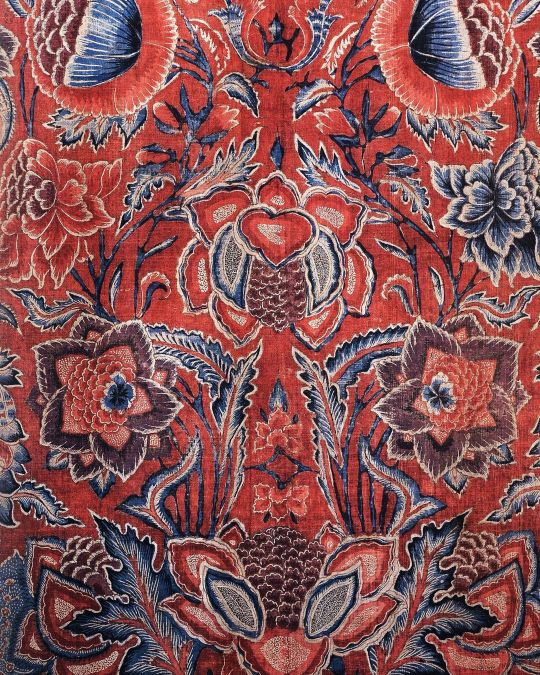

Fragment of a floor cover (India, Mughal dynasty, late 17th or early 18th century).

Painted and dyed cotton.

Image and text information courtesy MFA Boston.

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

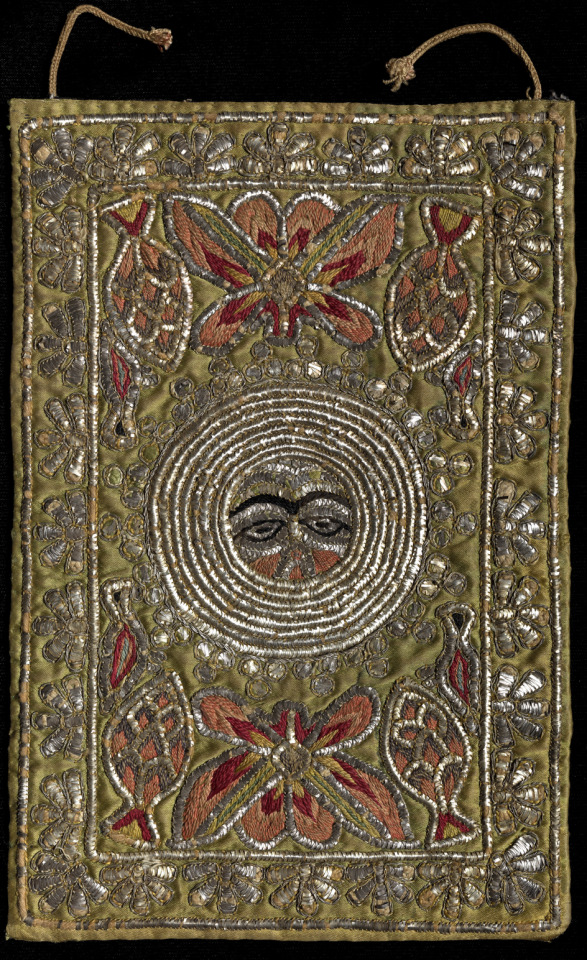

embroidered textile, silk gold and silver thread on satin, india, 1800s.

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

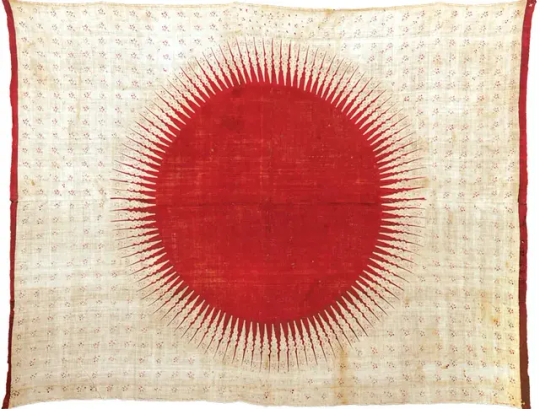

Ceremonial cloth with mata hari (‘eye of the day’) design, 18th or 19th century, Coromandel Coast, India, dyes and mordants on cotton.

270 x 240 cm

Apollo Magazine / Collection of Karun Thakar

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cotton skirt-cloths produced in India for the Thai market in the 19th century. Cloth of this nature was made-to-order by Indian craftspeople, and combined Indian and Thai textile technologies with Thai motifs. Several of these cloths have been created using mordant-dyeing and draw-resist techniques; the gold paint in the first, fourth, and last cloths was probably added in Thailand.

Mordant-dyeing is a technique that uses natural dye alongside a dye fixative—in this case, a metallic salt—to chemically bind the colorant to the cloth, and produce more permanent colours.

In resist-dyeing, some areas of the fabric are covered to prevent them from taking on any dye. A drawn resist technique uses a resist, such as wax, mud, gum, or resin, that is drawn onto the fabric.

A resist-dyeing technique may also be combined with a block-printing technique: in which case, a resist is applied to a carved block or stencil, and then pressed onto the fabric.

Contrast these colours and patterns with those on cloth intended for the English and Dutch markets.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

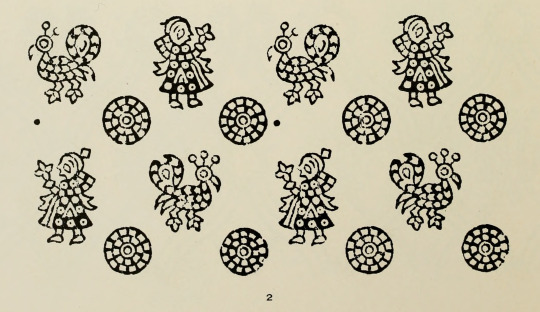

Textile pattern. Block prints from India for textiles. 1924.

Internet Archive

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

[T]he Dutch Republic, like its successor the Kingdom of the Netherlands, [...] throughout the early modern period had an advanced maritime [trading, exports] and (financial) service [banking, insurance] sector. Moreover, Dutch involvement in Atlantic slavery stretched over two and a half centuries. [...] Carefully estimating the scope of all the activities involved in moving, processing and retailing the goods derived from the forced labour performed by the enslaved in the Atlantic world [...] [shows] more clearly in what ways the gains from slavery percolated through the Dutch economy. [...] [This web] connected them [...] to the enslaved in Suriname and other Dutch colonies, as well as in non-Dutch colonies such as Saint Domingue [Haiti], which was one of the main suppliers of slave-produced goods to the Dutch economy until the enslaved revolted in 1791 and brought an end to the trade. [...] A significant part of the eighteenth-century Dutch elite was actively engaged in financing, insuring, organising and enabling the slave system, and drew much wealth from it. [...] [A] staggering 19% (expressed in value) of the Dutch Republic's trade in 1770 consisted of Atlantic slave-produced goods such as sugar, coffee, or indigo [...].

---

One point that deserves considerable emphasis is that [this slave-based Dutch wealth] [...] did not just depend on the increasing output of the Dutch Atlantic slave colonies. By 1770, the Dutch imported over fl.8 million worth of sugar and coffee from French ports. [...] [T]hese [...] routes successfully linked the Dutch trade sector to the massive expansion of slavery in Saint Domingue [the French colony of Haiti], which continued until the early 1790s when the revolution of the enslaved on the French part of that island ended slavery.

Before that time, Dutch sugar mills processed tens of millions of pounds of sugar from the French Caribbean, which were then exported over the Rhine and through the Sound to the German and Eastern European ‘slavery hinterlands’.

---

Coffee and indigo flowed through the Dutch Republic via the same trans-imperial routes, while the Dutch also imported tobacco produced by slaves in the British colonies, [and] gold and tobacco produced [by slaves] in Brazil [...]. The value of all the different components of slave-based trade combined amounted to a sum of fl.57.3 million, more than 23% of all the Dutch trade in 1770. [...] However, trade statistics alone cannot answer the question about the weight of this sector within the economy. [...] 1770 was a peak year for the issuing of new plantation loans [...] [T]he main processing industry that was fully based on slave-produced goods was the Holland-based sugar industry [...]. It has been estimated that in 1770 Amsterdam alone housed 110 refineries, out of a total of 150 refineries in the province of Holland. These processed approximately 50 million pounds of raw sugar per year, employing over 4,000 workers. [...] [I]n the four decades from 1738 to 1779, the slave-based contribution to GDP alone grew by fl.20.5 million, thus contributing almost 40% of all growth generated in the economy of Holland in this period. [...]

---

These [slave-based Dutch commodity] chains ran from [the plantation itself, through maritime trade, through commodity processing sites like sugar refineries, through export of these goods] [...] and from there to European metropoles and hinterlands that in the eighteenth century became mass consumers of slave-produced goods such as sugar and coffee. These chains tied the Dutch economy to slave-based production in Suriname and other Dutch colonies, but also to the plantation complexes of other European powers, most crucially the French in Saint Domingue [Haiti], as the Dutch became major importers and processers of French coffee and sugar that they then redistributed to Northern and Central Europe. [...]

The explosive growth of production on slave plantations in the Dutch Guianas, combined with the international boom in coffee and sugar consumption, ensured that consistently high proportions (19% in 1770) of commodities entering and exiting Dutch harbors were produced on Atlantic slave plantations. [...] The Dutch economy profited from this Atlantic boom both as direct supplier of slave-produced goods [from slave plantations in the Dutch Guianas, from Dutch processing of sugar from slave plantations in French Haiti] and as intermediary [physically exporting sugar and coffee] between the Atlantic slave complexes of other European powers and the Northern and Central European hinterland.

---

Text above by: Pepijn Brandon and Ulbe Bosma. "Slavery and the Dutch economy, 1750-1800". Slavery & Abolition Volume 42, Issue 1. 2021. [Text within brackets added by me for clarity. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#these authors lead by pointing out there is general lack of discussion on which metrics or data to use to demonstrate#extent of slaverys contribution to dutch metropolitan wealth when compared to extensive research#on how british slavery profits established infrastructure textiles banking and industrialisation at home domestically in england#so that rather than only considering direct blatant dutch slavery in guiana caribbean etc must also look at metropolitan business in europe#in this same issue another similar article looks at specifically dutch exporting of slave based coffee#and the previously unheralded importance of the dutch export businesses to establishing coffee mass consumption in europe#via shipment to germany#which ties the expansion of french haiti slavery to dutch businesses acting as intermediary by popularizing coffee in europe#which invokes the concept mentioned here as slavery hinterlands#and this just atlantic lets not forget dutch wealth from east india company and cinnamon and srilanka etc#and then in following decades the immense dutch wealth and power in java#tidalectics#caribbean#archipelagic thinking#carceral geography#ecologies#intimacies of four continents#indigenous#sacrifice zones#slavery hinterlands#european coffee#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Banjara

101 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We thought some color might be welcome on a dreary day in Cambridge. Here are some lovely images we found in 𝐖𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐂𝐚𝐫𝐠𝐨𝐞𝐬: 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐓𝐞𝐱𝐭𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐄𝐚𝐬𝐭 (New York, 1998). #textiles #rugs #India #Indonesia #Thailand #library #books #bookstagram #booksofinstagram #librarybooks #librarybooks (at Harvard Yard) https://www.instagram.com/p/Co8G4iqu0rk/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rogan is an technique of cloth printing practiced in the Gujarat, Peshawar and Sindh regions of India and Pakistan. The word rogan has roots in both Persian and Sanskrit, meaning oil. In this craft, paint is made from boiled castor oil or linseed oil and vegetable dyes is laid down on fabric using a stylus.

The process of applying this oil based paint to fabric was developed among the Khatri community in Gujarat and the techniques of preparing and applying dyes was passed down in the family. As rogan printed cloth tended to be less expensive than other heavily embroidered garments but could still produce the illusion of embroidery, it was the wedding garment of choice for women from poorer families. The craft nearly died out in the late 20th century with the availability of cheaper and machine-made textiles. However, it is currently being revived mostly due to the efforts of the artist Abdulgafur Khatri and his family, who work tirelessly to spread awareness about Rogan art and teach it to young people, mostly young women from poor families in order to empower them by providing a means of livelihood as well as keeping the art of rogan alive.

1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 8 / 9 / 10 / 11 | textile series

#ots#textiles#indian textiles#textile history#textile art#art printing#rogan art#gujarat#india#pakistan#south asia#desi tumblr#desiblr#sindh#peshawar#desi tag

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

'Mata Hari' ceremonial cloth (C18th/19th)

Made on the Coromandel Coast, India for the Indonesian market and found in Sulawesi, Indonesia

A ceremonial cloth bearing a radiating red sun or eye-of-the-day. Chintz, hand-painted centre, printed outer decoration: resist and mordant-dyed on cotton 2.7 x 2.04m

Karun Thakar Collection

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

fragment of a wool rug or garment, patterned in stripes and wang 王 (king) characters crossed by contrasting colors. taken from the ruins of niya 尼雅 (recorded in han records as jingjue 精絕), a former oasis state near khotan in modern xinjiang. excavated in 1900 or 1901 by british archeologist aurel stein. three kingdoms era or western/eastern jin dynasty, 3rd century-4th century.

white s-plied two-ply warp, single-ply z-twist weft in yellow, blue, green, red, and rose. the green and red stripes are done in plain weave with single weft; the 王 crosses and the staggered boxes (lower left photo) are done in double weft. the crosses use discontinuous tapestry weave. the british museum notes that this textile may have been produced in india.

#china#three kingdoms era#western jin dynasty#eastern jin dynasty#textile history#museum trawling#image source: british museum#aurel stein#i see what they're getting at - the stripes are not very jin dynasty - but the crossed ��� characters do not necessarily say 'india' to me

64 notes

·

View notes